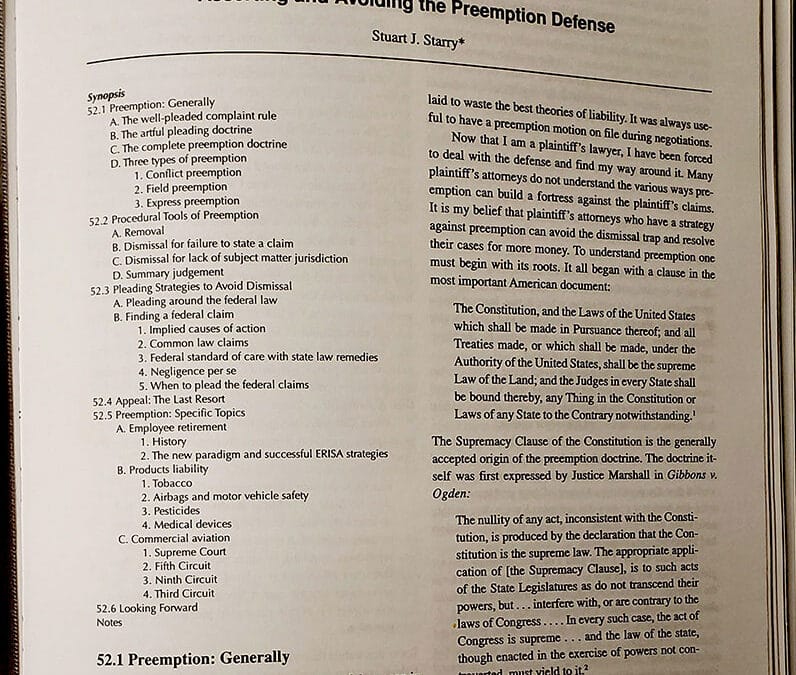

XX Asserting and Avoiding the Preemption Defense

By Stuart Starry*

XX.1 Preemption: Generally

When I was a defense lawyer, the most powerful weapon in my arsenal was the preemption defense. On several occasions I totally annihilated my opponents by obtaining outright dismissals of their cases. On many more occasions I laid to waste the best theories of liability. It was always useful to have a preemption motion on file during negotiations.

Now that I am a plaintiff’s lawyer, I have been forced to deal with the defense and find my way around it. Many plaintiff’s attorneys do not understand the various ways preemption can build a fortress against the plaintiff’s claims. It is my belief that plaintiff’s attorneys who have a strategy against preemption can avoid the dismissal trap and resolve their cases for more money. To understand preemption one must begin with its roots. It all began with a clause in the most important American document:

The Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.1

The Supremacy Clause of the Constitution is the generally accepted origin of the preemption doctrine. The doctrine itself was first expressed by Justice Marshall in Gibbons v. Ogden:

The nullity of any act, inconsistent with the constitution, is produced by the declaration that the Constitution is the supreme law. The appropriate application of [the Supremacy Clause], is to such acts of the State Legislatures as do not transcend their powers, but . . . interfere with, or are contrary to the laws of Congress . . . . In every such case, the act of Congress is supreme . . . and the law of the state, though enacted in the exercise of powers not controverted, must yield to it.2

The power of this clause invades many aspects of a trial lawyer’s practice. The practical significance is often best demonstrated by anecdote.

Some time ago I had the privilege of representing a major air carrier. The major air carrier only flew between larger cities, but it desired to generate additional business by offering the passengers “through transportation” to ski resorts near smaller towns. Smaller regional air carriers who flew smaller planes serviced the smaller towns. Ticket code sharing provided the vehicle for the major carrier to provide such “through transportation” to the smaller towns. Under this arrangement, a passenger’s ticket would show the same, two-letter airline designation code regardless of whether the passenger flew on the major or a regional carrier. Not only did the airlines share ticket codes; they also shared trademarks and logos. The smaller carriers even painted their planes with markings and colors identical to the major airlines. When a passenger of the major carrier landed in Denver and then boarded a smaller plane to the ski resort, it was an invisible transition. Most passengers never realized they were on a different airline when they boarded the smaller plane.

Unfortunately, one of the small planes crashed, killing the pilot, copilot, and several passengers. Tragedy turned to horror during the investigation when it was learned that a blood test of the pilot’s body revealed he had used cocaine shortly before the crash. This was a dream case for the plaintiffs. It was an impossible case to defend.

For the plaintiffs, the case got even better. It was filed in state court and was assigned to a judge who was a personal friend to one of the crash victims. The case was filed against both the regional carrier and the major carrier.

After months of discovery it was learned that the regional carrier, who employed the pilot, had not conducted a background check. A background check would have revealed that the pilot had a history of drug problems. Moreover, the regional carrier did not even have a drug testing policy for its flight crews-something that major carriers had implemented for decades.

Needless to say, I was glad I did not represent the regional carrier. My goal was to distance the major carrier from the wrongful conduct. After all, the major carrier had a strict drug policy and conducted thorough background checks.

The plaintiffs’ problem was that they had to get past the financial limitations of the regional carrier to recover a substantial sum. The regional carrier had only a few leased planes and minimal insurance coverage. My defense team estimated that the case was worth over $10 million on a good day and at least $3 million on a bad day. The plaintiffs needed a theory of liability against the major carrier, who they knew had deep pockets. They found one. They claimed that the major airline and the regional airline conspired to defraud the public through the ticket coding and trademark sharing arrangement. The survivors testified that they thought they were flying on the major airline at the time of the crash. They also assumed that the pilots on the small airplanes had the same qualifications and training, as did the pilots on the big planes. Otherwise, they would not have boarded the smaller plane.

The plaintiffs’ pleading was amended to add fraud and a claim under the state’s deceptive trade practices act (which, at the time, allowed automatic trebling of damages). By now my trial team was really worried. We took the plaintiffs’ new theory to a group of mock juries. The lowest verdict was for $18 million. Many were over $100 million in punitive damages. We were terrified at the prospect of a trial. Because the case was lodged in a plaintiff-friendly court, we expected the worst. The trial judge denied a recusal motion, and it looked as though the plaintiffs wanted to try the case to a jury and roll the dice on punitive damages.

Fortunately, within a short time after the pleading was amended, we discussed a removal strategy based on federal preemption. My partners thought it was a hair-brained strategy and predicted that the case would be remanded. I was desperate and undeterred. One of the plaintiffs’ expert witnesses testified that the ticket coding and trademark sharing was not only fraudulent but was also sanctioned by the federal government as part of airline deregulation. The government’s policy was aimed at reducing fares and opening up smaller routes to the public. The plaintiff’s expert had been pressing for a change in the Airline Deregulation Act.

When Congress deregulated the airlines, they enacted a preemption provision designed to prevent state re-regulation:

Except as provided in paragraph (2) of this subsection, no State or political subdivision thereof and no interstate agency or other political agency of two or more states shall enact or enforce any law, rule, regulation, standard, or other provision having the force and effect of law related to rates, routes, or services of any air carrier having authority under subchapter IV of this chapter to provide air transportation.3

It was this statute that was our savior. We removed the case to federal court on federal question grounds, claiming that federal law applied exclusively to the plaintiffs’ fraud claim because it related to air carrier’s “rates and routes.” After all, the plaintiffs’ own expert had testified that code sharing allowed the larger carriers to economically service smaller routes.

At the hearing on the inevitable motion to remand, the court inquired whether I was the one who signed the removal papers. I replied: “Yes.” The trial judge then reminded me that I was the one who would be sanctioned if he found the removal grounds to be frivolous. After several hours of creative argument (without the benefit of supporting case law), the court took the matter under advisement. A week later the trial judge issued an opinion retaining jurisdiction.

We then filed a motion to dismiss the claim because federal law had no similar remedies for such fraud. There was no federal deceptive trade practices act. There was no federal common law of fraud. The case was then settled for a mere fraction of its value in state court. It was a victory for the defense. Had my opponent known that his creative pleading would land him in federal court, he certainly would not have added the fraud claim.

My experience with the strategic removal of the case taught me a very important lesson. Before a pleading is filed, a good practitioner must always ask: “Does federal or state law control the case?” The answer should be an easy one. It generally is not. Federal preemption analysis is a jigsaw puzzle, and it often it seems Congress left out some vital pieces. At the initial stages of any case, it is important to establish whether a preemption question exists.

Under normal circumstances, a plaintiff is the master of his complaint. Simply because federal relief is available does not mean that a plaintiff is required to use federal relief. Often a plaintiff is in a better position in state court asserting only state law claims. If a state law claim exists concurrently with a federal claim, a plaintiff may choose to use the state law claim in lieu of or in addition to, the federal claim. A defendant may be in a better position under federal law. To properly assert and defend preemption claims, practitioners must understand several doctrines.

A. The Well Pleaded Complaint Rule

A plaintiff can generally keep his claim in state court as long as he is careful not to base his claim on any federal cause of action. Mere anticipation of a federal defense is not enough to force the claim into federal court. The Supreme Court first addressed a plaintiff’s duty to clearly state his claim in Louisville & Nashville R. R. v. Mottley.4 In that case Justice Moody declared on behalf of the court that

[A] suit arises under the Constitution and laws of the United States only when the plaintiff’s statement of his own cause of action shows that it is based upon those laws or that Constitution. It is not enough that the plaintiff alleges some anticipated defense to his cause of action and asserts that the defense is invalidated by some Provision of the Constitution of the United States.5

Mottley is the basis for the well pleaded complaint rule. Most simply stated, if a plaintiff wants to be in federal court, he must allege a federal cause of action. If he prefers to be in state court, he needs to avoid alleging a federal cause of action. His motive for wanting to be in either forum is irrelevant. However, like all rules of law, this has an exception: the artful pleading doctrine.

B. The Artful Pleading Doctrine

The artful pleading doctrine holds that an attorney cannot overrule legislative intent simply because he is crafty. In circumstances where it is clear that Congress intended to preempt state law, no amount of artful pleading will keep the case out of a federal forum. The Ninth Circuit may have stated this principle most succinctly when it delivered the following: “Although a plaintiff is generally considered the master of his complaint and is free to choose the forum for his action, this principle is not without limitation. A plaintiff will not be allowed to conceal the true nature of a complaint through ‘artful pleading.'”6 As a law professor once explained to me and a class of eager first-year law students: “If you paint the word ‘cow’ on the side of a horse, that doesn’t make it a cow.” The troublesome task for most practitioners is seeing the horse in the first place. That was the problem for the plaintiff’s attorney in the ticket code-sharing case discussed earlier. What he thought was a state law claim was actually covered by federal laws so powerful that they governed his complaint. This principle was stated another way by the court in Stewart v. American Airlines.7 “The preemptive force of certain federal statutes is so great that they convert otherwise ordinary state law claims into federal claims for the purposes of the ‘well-pleaded complaint rule.'”8Although one can argue either that the claim was converted to federal law or that it was always federal law, the result is the same: a complete difference in the governing law and a possible change of forums.

C. The Complete Preemption doctrine

Those who wish to invoke the artful pleading doctrine offensively against an opponent’s “crafty” pleading should be careful as well. The doctrine itself has limits. Just because a plaintiff’s claim touches a federally regulated area does not mean it is preempted. A loose connection with federal law is not enough to send a case to a federal court when Congress clearly did not intend for federal law to control such a case. The Court in Merrill Dow Pharmaceutical Inc. v. Thompson,9 concluded that

. . . a complaint alleging a violation of a federal statute as an element of a state cause of action, when Congress has determined that there should be no private, federal cause of action for the violation, does not state a claim “arising under the Constitution, laws or treaties of the United States.”10

Federal principles must control the disposition of the claim, not merely be associated with the claim.11 This is the complete preemption doctrine and is a corollary to the artful pleading doctrine. However, if the claim is completely preempted, then, an artfully crafted state law claim is converted to a federal claim for removal purposes.12

In sum, these three principles mean the following: A plaintiff can avoid preemption by pleading a state law claim that does not touch upon federal law. Even if the defendant asserts that the claim is preempted, the defense of preemption does not render the case removable. It is only when the preemption is so “complete” that the plaintiff must rely on federal legal principles to recover, that the case is converted to a federal one and becomes removable.

D. Three Types of Preemption

Preemption is generally divided into three categories: (1) conflict preemption, (2) field preemption, and (3) express preemption. Every American trial lawyer should be aware of all three.

1. Conflict Preemption

Conflict preemption was the first type of preemption to be recognized by the courts.13 It most closely follows the ideology set forth by the Supremacy Clause. It occurs when state law conflicts with federal law. When it is impossible to comply with both state and federal law, the federal law governs. Consider the situation that might arise if, for example, the Ohio state legislature outlawed the use of airbags in automobiles because it was reported that some deaths were actually being caused by airbags. A car manufacturer in Ohio may be faced with the prospect of violating the federal law mandating the installation of airbags in order to comply with the state legislature’s wishes. In a claim to enforce the ban, courts would be obliged to enforce the federal law, and ignore the state law.

Sometimes, seemingly contradictory laws do not create preemption by conflict. Early in the history of preemption analysis, the Supreme Court in Savage v. Jones established that the conflict needs to be “so direct and positive that the two acts cannot be reconciled or stand together.”14 If, for example, the Ohio legislature merely required that all cars equipped with airbags have switches allowing drivers to disable the airbags, then the law may not conflict with a federal law requiring the installation of airbags. The laws may seem at cross-purposes, but in fact, compliance with both is possible, and there is no conflict for federal preemption to resolve.

2. Field Preemption

The birth of field preemption was spawned by the cases of Hines v. Davidowitz15 and Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp.16 When a state tries to regulate an area that Congress intended the federal government to fully occupy, the state regulation is preempted. For such preemption to occur, the federal regulation must be “so pervasive as to make reasonable the inference that Congress left no room for the states to supplant it.”17 In Hines, the Supreme Court determined that the Federal Alien Registration Act of 1940, along with the federal immigration and naturalization laws provided a comprehensive scheme for the regulation of aliens. Thus, an act passed by the Pennsylvania legislature requiring alien registration was void.18

When the area is one that the states have traditionally occupied, the requirements for both conflict preemption and field preemption are more stringent. When the tradition is one of state occupation, then the field will only be preempted if there is evidence of “clear and manifest intent” by Congress to do so. Courts are reluctant to find preemption in areas of traditional state power because doing so seems to undermine the federalist system.19 If Congress had not expressly stated an intent to preempt, then it becomes difficult to find the evidence of “clear and manifest intent” to preempt. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court in Rice found that it is possible to find clear and manifest intent through an assessment of congressional purpose.20 The Rice Court held enforcement of several state laws preempted by the comprehensive nature of the Federal Warehousing Act. The Court looked to the language in the act conferring “exclusive” authority with the Secretary of Agriculture, along with statements of sponsors found in committee reports that federal licensees would be “solely responsible to the Federal act.”21An assessment of congressional purpose, though, is not a simple undertaking. In order to assure that the bounds of state sovereignty will not be infringed, courts often read field preemption as narrowly as possible.22 This author has failed to ever convince any trial or appellate court that any area of law has been “occupied” to the extent necessary for preemption of state law.

Field preemption, however, is not completely unheard of. When it occurs, its force is broad and displaces even consistent state law. The First Circuit recognized it in French v. Pan Am Express, Inc.23 Very recently in Abdullah v. American Airlines, the Third Circuit followed the reasoning of French that

. . . the lack of a conflict between federal standards and state law is irrelevant. The court in French remarked that the absence of a conflict was “beside the point.” “So long as occupation of an envisioned field was intended, ‘any state law falling within the field is pre-empted.’ . . . The federal interest necessarily predominates, rendering states impotent to act.”24

Before attempting to assert field preemption arguments, you should be thoroughly familiar with the statues, regulations and legislative history of the federal laws asserted.

3. Express Preemption

Congress often uses statutory language to express its intent to preempt state regulation of a particular area of law. This “express preemption” should be the easiest to recognize. However, in recent years practitioners have been forced to navigate an extremely complex group of United States Supreme Court decisions on the matter. The sheer number of plurality decisions handed down from the Supreme Court has made express preemption analysis difficult to understand.25

As with any statutory construction analysis, opposing sides can read the same words and interpret them differently. The microanalysis of individual words has lead to conflicting decisions regarding nearly identical statutes. In the example involving the ticket code-sharing airlines, the operative words from the preemption statute at hand were “relating to rates or routes.” In nearly all express preemption analyses one will encounter a key phrase. Winning a case, many times, involves a lawyer convincing the court that his definition of that phrase is the correct one.

How the court determines the “correct” definition often requires examination of congressional intent. This examination, articulated by the Supreme Court in Medtronic v. Lohr, should be done “through the reviewing court’s reasoned understanding of the way in which congress intended the statute, and its surrounding regulatory scheme to affect business consumers and the law.”26 This examination clearly can include examination of not only the language of a statute but can also include analysis of the surrounding text and context. This author’s experience with appeals based on express preemption is instructive. In the field of commercial aviation, Congress enacted a preemption provision that has been given very different interpretations by both the Fifth and Ninth Circuits. See discussion of aviation law infra at p.__

Often courts revert to the “congressional purpose” analysis used in field preemption merely to define the term of an express preemption clause.27

XX.2 Procedural Tools of Preemption

If an attorney suspects that his case is preempted by federal law, the next step is deciding which procedural device to use (or avoid) to advance his client’s interests. There are several.

A. Removal

The federal removal statute reads:

(a) Except as otherwise expressly provided by Act of Congress any civil action brought in a State court of which the district courts of the United States have original jurisdiction, may be removed by the defendant or the defendants, to the district court of the United States for the district and division embracing the place where such action is pending. . . .

(b) Any civil action of which the district courts have original jurisdiction founded on a claim or right arising under the Constitution treaties or laws of the United States shall be removable without regard to the citizenship or residence of the parties. Any other such action shall be removable only if none of the parties in interest properly joined and served as defendants is a citizen of the State in which such action is brought.

(c) Whenever a separate and independent claim or cause of action within the jurisdiction conferred by § 1331 of this title is joined with one or more otherwise non-removable claims or causes of action, the entire case may be removed and the district court may determine all issues therein, or, in its discretion, may remand all matters in which State law predominates.28

Before a plaintiff files his case in state court he should determine whether there is any chance that the defendant could remove the case to federal court. Often plaintiffs mistakenly cite federal statutes that the defendant violated in their initial pleadings. Even if a plaintiff is only pleading negligence under state law and merely using the federal statute as a basis for a state law negligence per se claim, federal courts will often construe it as a federal claim. If a plaintiff wants to avoid federal court, I recommend that no federal statutes be cited.

If one is compelled to cite a federal law as evidence of negligence per se, then the pleading must contain the following language in the jurisdiction section: “Plaintiff does not herein assert any federal claim, and any reference to federal law is merely exemplary. Because of this disclaimer any attempt to remove this case by the defendant is necessarily frivolous.” This disclaimer should give a defendant pause before any removal papers are filed. Unfortunately, it is not a guarantee that the defendant will not successfully remove the case. If the area of law in which the claim is asserted is “completely” preempted, then the case is removable notwithstanding the disclaimer. In other words, if the case is a federal “horse,” then painting a state law “cow” on the side of it will not fool a federal judge.

A defendant who desires to put his opponents in federal court needs to be knowledgeable about the substantive law in the arena under which the case arises. If he is in unfamiliar territory he should conduct substantive research before the applicable removal deadline. After the research, the analysis is simple. Every claim made by the plaintiff presupposes that the defendant could have avoided the lawsuit by conducting himself differently. The existence of the claim, then, has the power to regulate conduct. Whatever the defendant should have done differently to avoid the lawsuit is the conduct expected by the claim’s regulation. If the conduct regulation imposed by the plaintiff’s state law claims: (1) conflicts with federal law, (2) falls in an area pervasively occupied by federal regulation, or (3) is expressly preempted by federal statute, then the case is removable. The real inquiry is: “What conduct is the plaintiff’s claim regulating?”

Often the wording of a plaintiff’s complaint can make a case vulnerable to this analysis. For example, assume an injured passenger sues an airbag manufacturer claiming in his pleadings that “the defendant was negligent in installing a dangerous airbag in the plaintiff’s car.” This pleading may be interpreted by the court as holding a manufacturer liable for installing a device required to be installed by federal law. In such a case, conflict preemption would make the case vulnerable to removal. On the other hand, the plaintiff may eliminate the removal threat by being more specific in the complaint. For example, pleading that “the defendant was negligent in failing to install a safe airbag in plaintiff’s car” would render the case immune from misinterpretation and removal. In the latter pleading language, it is clear that the conduct imposed by the claim (installing a safe airbag) is not in conflict with the federal law requiring airbags. It merely asks that the airbags installed pursuant to federal law be safe ones.

In sum, care must be taken by the plaintiff to craft a pleading to avoid removal anytime the claim nears federally regulated territory.

B. Dismissal for Failure to State a Claim

The best way to avoid a Rule 12(b)(6) motion is to stay out of federal court. But, when a case has been removed from state court or filed originally in federal court it remains vulnerable to a Rule 12(b)(6) motion if the state law claims have been preempted.29 This is because federal law is almost all statutory in nature (with few exceptions such as admiralty). As a result, federal law has few remedies for most common types of wrongful conduct (i.e., negligence). Often times even if an area is exclusively in the federal domain, there is no remedy for the wrongful conduct alleged. In the airbag case example, the court would dismiss a claim of negligently installing an airbag, because there is no federal negligence law and the federal statutes do not create a cause of action to redress such conduct. One can assert that failure to provide a remedy is unconstitutional, but often a court would prefer to dismiss the case, rather than assume the burden of crafting a federal remedy.

This author exploited that very situation representing the airline in Baugh v. TWA.30 In Baugh, a flight attendant with high heels stepped on the plaintiff, breaking her ankle. I removed the case on diversity grounds and then filed a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim under Rule 12(b)(6).

When I took the plaintiff’s deposition, I was mindful to use magic words from the preemption statute during cross-examination. I got her to agree that her injuries occurred during the flight attendant’s attempt to provide meal “service.” This was important because all state regulation of an air carrier’s “rate, routes, and services” had been expressly preempted by statute. I took the position that the claim would require the defendant airline to prohibit flight attendants from wearing high heels and serving in-flight meals during turbulence. A good idea perhaps, but state regulation of conduct nonetheless. The court agreed and granted the motion to dismiss. The biggest mistake made by the plaintiff’s attorney was his failure to assert a federal claim after removal. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal and did not have to reach the issue of whether federal remedy existed.31 Even though it was not clear whether federal law provided a remedy, pleading one would have forced the court to entertain the issue of whether a federal claim existed or whether to deny the plaintiff any remedy whatsoever. Anytime there is a preemption defense, the plaintiff should counter that federal remedies are implied or arise under federal common law. At least then the court will have to ponder depriving the victim of a remedy.

C. Dismissal for Lack of Subject Matter Jurisdiction

Ironically, a circuitous logical matrix emerges when analyzing removal jurisdiction and lack of subject matter jurisdiction. In a non-diversity case, if only state law claims are pled and they are not preempted, then they cannot be asserted in federal court. Any attempt to file such claims in federal court would face dismissal for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. However, if the same claims were preempted, the case could be removed if it were originally filed in state court. Then, the federal court could dismiss the whole case under Rule 12(b)(1) if federal law provided no remedy. Query: If the lawsuit were dismissed for failure to state a claim, just what was the federal court asserting removal jurisdiction over in the first place? The “claims or rights” are either “arising under the Constitution treaties or laws of the United States” (in which case they are cognizable) or they do not so arise (in which case they are not removable). That is a conflict that has bothered this author for many years and has no answer.

In any event, most federal courts will assume jurisdiction over the subject matter if the preemption issue is brought forth. A removing defendant would be better suited to bring all dismissal motions as Rule 12(b)(6) motions, rather than Rule 12(b)(1) motions. This avoids the circuitous logic problem. However, in certain instances a defendant can only rely on a Rule 12(b)(1) motion in the preemption game. An important example of this is in order.

This author had the pleasure of losing his first trial in a dramatic way. The case was O’Carrol v. American Airlines.32 In O’Carrol, the plaintiff had been removed from the airplane by the flight crew on charges of intoxication and unruly behavior. He was arrested by the airport police and spent an unpleasant night in jail. He sued the airline, asserting state law claims of assault and battery, false imprisonment and false arrest. The plaintiff brought the claims originally in a Beaumont, Texas, federal court on diversity grounds. At that time, federal court in Beaumont was considered a plaintiff’s nirvana. Despite the forum, a naive sense of bravado and encouragement from my mentors convinced me to take the case to trial. Unfortunately, I was dismantled at the trial by a board-certified attorney with 20 years experience. I had approximately nine months of law practice under my belt, none of which was in a courtroom. The jury returned a verdict of $272,000 in the plaintiff’s favor. Many long nights in the library were spent trying to salvage my big firm career. Then it hit me – Preemption. During the trial I had argued that federal law required the captain to remove anyone who appeared to be intoxicated from the plane. Thus, the reasoning went, he couldn’t have been negligent. I was right. The problem was that I argued it to the jury and it was a matter for the judge. How could I get my preemption argument heard after trial? As a general proposition jurisdiction is never waived. Under the federal rules of civil procedure, a Rule 12(b)(1) motion can be argued even after trial.33 I promptly filed the motion and argued that the entire trial was for naught. The court lacked subject matter jurisdiction over the claims that were tried, because they were state law claims that had been preempted. Although the trial court denied the motion, it preserved the argument for appeal. Ultimately the Fifth Circuit agreed with me and vacated the judgment.34 It was a total victory for the defense, which could have only been accomplished through Rule 12(b)(1).

D. Summary Judgment

Because many state judicial systems differ procedurally from the federal system, Rule 12(b)(6) and Rule 12(b)(1) procedural devices are often unavailable when asserting preemption arguments in state courts. This author has generally observed preemption arguments to be brought in the form of summary judgment motions in such instances.35 Substantively, there is no difference. The federal motions are generally considered as dispositive as a summary judgment.

XX.3 Pleading Strategies to Avoid Dismissal

A. Pleading Around the Federal Law

The simplest way to avoid preemption is to avoid pleading claims that regulate conduct governed by federal law. A boilerplate pleading of state law negligence is not enough. One must know the substance of any federal laws that may apply. Pleading negligence without knowing the federal law is like walking through a minefield wearing a blindfold. Remember the defective airbag example. The only way a plaintiff’s attorney could know the wisdom in pleading negligent “failure to install a safe airbag” (not preempted) and negligent “installation of a dangerous airbag” (preempted) was to know that federal law required their installation.

Know the applicable federal laws and only describe wrongful conduct that could have been engaged in despite the federal law. Despite the state law legal theory (negligence, strict liability, warranty, or contract), if the wrongful conduct described by the pleadings is either required by federal law encouraged by federal law or even covered by federal law, it is preempted.

B. Finding a Federal Claim

If the conduct regulated by ones claims appears to be preempted, the one must search the fact of the case for other wrongful conduct. If non-preempted conduct can support liability and causation, it should be used to plead around the federal law. However, if the only wrongful conduct legitimately causing plaintiff’s damages is governed exclusively by federal law, then one must find a federal remedy or send the client home to lick his wounds.

1. Implied Causes of Action

The most common method of creating a federal claim is to imply one under the relevant federal statutes according to the doctrine of Cort v. Ash.36 In determining whether a private cause of action exists, Cort v. Ash, sets forth factors which are relevant. They are as follows:

1. Is the person one of a class for whose special benefit the statute was enacted; that is, does the statute create a federal right in favor of the plaintiff?

2. Is there any indication of legislative intent, explicit or implicit, either to create such a remedy or to deny one?

3. Is it consistent with the underlying purposes of the legislative scheme to imply such a remedy for Plaintiff?

4. Is the cause of action one traditionally relegated to state law in an area basically the concern of the state so that it would be inappropriate to infer a cause of action based solely on federal law?37

Applying these factors in the shadow of a preemption claim is not difficult. With respect to the first factor, most statutes are designed to protect the public, and usually, the plaintiff is a member of the class Congress was trying to protect. For example, if the plaintiff was poisoned by federally regulated chemicals, then in all likelihood, the regulations were designed to prevent the poisoning.

With respect to the second factor, most statutes do bear some assumption of a private remedy. Most regulatory statutes contain “savings clauses” designed to preserve remedies which pre-dated the legislation. Some statutes have liability insurance requirements which, obviously, assume lawsuits may be filed. Most of the time, if one scours the text of a statute and its legislative history, one can find a language to somewhat satisfy this factor.

With respect to the third factor, it is almost always consistent with the purpose of a statute to penalize violations of the statute with lawsuits. The fourth factor is the easiest. It is always satisfied in the shadow of a preemption claim. If the area is preempted, then it cannot possibly be “relegated to state law.” Therefore, it would always be appropriate to imply a cause of action.

In pleading an implied cause of action, this author recommends setting forth the statutory language relied upon and citing Cort. Then a court could hardly find that pleading failed to state a claim. Rather, the court would be required to determine if the claim is one “upon which relief can be granted.”

2. Common Law Claims

The law presumes a remedy for a wrong done. The United States Supreme Court has declared:

Rights, Constitutional and otherwise, do not exist in a vacuum. Their purpose is to protect persons from injuries to particular interests, and their contours are shaped by the interests they protect.

Our legal system’s concept of damages reflects this view of legal rights. “The cardinal principal of damages in Anglo-American law is that of compensation for the injury caused to plaintiff by defendant’s breach of duty.” 2 F. Harper & F. James, Law of Torts § 25.1, p. 1299 (1956) (emphasis in original).38

This principle of American law is the philosophical bedrock upon which all common law rests. It is also a last resort for one who’s claims seem to be preempted and who cannot find a federal statute granting or even implying relief. Courts rarely recognize federal common law claims. But if failure to do so would be obviously unjust, federal courts may be willing to recognize federal common law under their constitutional authority.39

Any time a plaintiff’s claims are removed on federal question grounds and there is clear preemption without a chance of remand, the plaintiff’s counsel should amend to allege that the plaintiff has a federal common law claim identical in nature to the state law claims pled. Then and only then will the court be required to contemplate the existence of a duty and a breach of that duty, prior to dismissal.

3. Federal Standard of Care with State Law Remedies

A final way for a plaintiff to admit the existence of federal preemption and preserve his client’s claims is to convince the court to adopt the reasoning of the Court in Silkwood v. Kerr-McGee Corp.40

In Silkwood a laboratory analyst at a federally licensed nuclear power plant was contaminated by plutonium. After she was killed in an unrelated car accident, the administrator of her estate brought a diversity action in federal court based on the Oklahoma common law of torts. After a favorable jury verdict, the court of appeals reversed, holding that the punitive damages awarded were preempted by the existence of the federal nuclear regulatory scheme. The Supreme Court reversed this holding on a unique basis. While admitting that the federal government had “occupied the entire field of nuclear safety concerns,” the Court pointed to the legislative history of the Atomic Energy Act for evidence that Congress left room for state law remedies.

This limited preemption was based mostly on the fact that Congress failed to provide for a federal remedy:

If there were nothing more, this concern over the states’ inability to formulate effective standards and the foreclosure of the states from conditioning the operation of nuclear plants on compliance with state-imposed safety standards arguably would disallow resort to state-law remedies by those suffering injuries from radiation in a nuclear plant. There is, however, ample evidence that Congress had no intention of forbidding the states from providing such remedies.

Indeed, there is no indication that Congress even seriously considered precluding the use of such remedies either when it enacted the Atomic Energy Act, in 1954 and or when it amended it in 1959. This silence takes on added significance in light of Congress’ failure to provide any federal remedy for persons injured by such conduct. It is difficult to believe that Congress would, without comment remove all means of judicial recourse for those injured by illegal conduct.41

While the trial court in Silkwood actually submitted the case on a negligence and a gross negligence charge from Oklahoma law, there was plenty of evidence that Kerr-McGee had violated federal regulations.42 In most respects, the negligence standard applied was no different than the federal regulations that required “reasonable” efforts to minimize exposure.43

Silkwood has been cited by subsequent decisions imposing a federal standard of care, while allowing state law remedies.44 Thus, one could argue that a finding of preemption does eliminate the application of inconsistent state tort standards of conduct. But if federal standards of conduct (or consistent state standards) are applied, then Congress’ intent to preempt is preserved, exclusive federal regulation is preserved. At the same time, a remedy for conduct violative of the federal standard is administered through state law damages. After all, the Court in Silkwood explained:

We do not suggest that there could never be an instance in which the federal law would preempt the recovery of damages based on state law. But insofar as damages for radiation injuries are concerned, preemption should not be judged on the basis that the federal government has so completely occupied the field of

safety that state remedies are foreclosed but on whether there is an irreconcilable conflict between the federal and state standards or whether the imposition of a state standard in a damages action would frustrate the objectives of the federal law. We perceive no such conflict or frustration in the circumstances of this case.

. . . .

The United States, as amicus curiae, contends that the award of punitive damages in this case is preempted because it conflicts with the federal remedial scheme, noting that the NRC is authorized to impose civil penalties on licensees when federal standards have been violated. 42 U.S.C. § 2282 (1976 ed. and Supp. V) However, the award of punitive damages in the present case does not conflict with that scheme. Paying both federal fines and state-imposed punitive damages for the same incident would not appear to be physically impossible. Nor does exposure to punitive damages frustrate any purpose of the federal remedial scheme.45

Pleading the “federal standard with state remedy” argument is simple. One should allege the violation of federal law in specific statutory or regulatory terms and state that “because of defendant’s violation of the federally imposed standard of care, plaintiff is entitled to a damage remedy at common law which is not precluded by the federal regulatory scheme.” Practitioners should not confuse such a claim with negligence per se (which ought to be pled in a separate count to avoid confusion). The former leaves no room for state law negligence while the latter is using federal law as a per se example of negligence, which could presumably in other instances vary from the federal standard.

4. Negligence Per Se.

While not a federal remedy, the state law doctrine of negligence per se can be asserted using violations of federal statutes and regulations as evidence of per se negligence under state law. The distinction between the “state law remedies with a federal standard of care” claim and a negligence per se claim based on the federal law is blurry to say the least. But practitioners should always plead them in separate counts to avoid confusing the courts. Most courts can easily grasp the concepts of negligence per se, but they may not grasp (or politically accept) the Silkwood rationale.

5. When to Plead the Federal Claims

Because most plaintiffs prefer to stay in state court, they should not initially plead federal claims unless they wish to be removed or wish to file in federal court from the beginning. Otherwise, these claims should only be added after a removal succeeds and an attempted remand fails.

This concept is true for negligence per se claims as well. Even though technically they are not claims based on federal law, few courts have the discipline to ferret out the difference. This author’s experience is that many courts can not grasp the idea that a pleading can cite violation of a federal law and not be asserting a federal claim. The risk of removal warrants avoiding it, unless absolutely necessary. See discussion of pleading disclaimer, supra p. ___.

XX.4 Appeal: The Last Resort

Most preemption motions are dispositive of either some or all of the issues in a case. Thus, they are likely to end up the subject matter of an appeal. There is a great deal of appellate authority on various aspects of preemption. As discussed earlier, there is no real clear-cut test for any of the three types of preemption. Thus, the appellate decisions usually hinge on policy objectives of the current politic and the composition of the appellate court. It is advisable to retain a preemption expert if your case is headed for an appeal on either side of a preemption battle.

XX.5 Preemption: Specific Topics

While it may seem that the remainder of this chapter need not be read from beginning to end, it should be. It is a survey of some of the most prominent cases in which the federal preemption defense has made law. The most significant preemption cases have been described in the areas of employee retirement, commercial aviation, medical devices, pesticides, and tobacco. However, there are many other areas in which one may find a preemption defense asserted, such as railroads, hazardous substances, general aviation, securities, copyright, to name a few.

This survey will reveal that most preemption law is based on express provisions in federal statutes. Such provisions commonly use two basic types of language. One type involves prohibiting states from imposing “requirements” that are “different from or in addition to” federal law. The other type involves prohibiting enforcement of state laws “relating to” a particular subject matter. Each of these two types of express preemption language has its own line of cases. One should always be careful not to use the wrong line of cases to support his argument.

A. Employee Retirement

1. History

In 1974, long before the current trend in managed health care began, Congress enacted the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (“ERISA”).46 ERISA touches nearly all employee benefits, from retirement to medical benefits, from COBRA47 plans to HMOs.48 The purpose was twofold: 1) employers would be encouraged to provide employees with appropriate fringe benefits unencumbered by many different state law requirements,49 and 2) employees would be protected from unscrupulous employers who were underfunding programs that wound up insolvent before the employee received any benefits.50

Section 514 of ERISA (now recodified at 29 U.S.C. § 1144)51 reads in part:

§ 1144. Other laws

(a) Supercedure; effective date. Except as provided in subsection (b) of this section, the provisions of this title and title IV shall supersede any and all State laws insofar as they may now or hereafter relate to any employee benefit plan described in section 4(a) and not exempt under section 4(b). This section shall take effect on January 1, 1975.

This is an express preemption provision. It appears to make every provision of ERISA displace state law so long as the state law “relates to” an employee benefit plan. One of the most troublesome provisions of ERISA, which displaces state law, is § 502.

Section 502 of ERISA (now recodified at 29 U.S.C. § 1132)52 reads in part:

§ 1132. Civil Enforcement

(a) Persons empowered to bring a civil action. A civil action may be brought-

(1) by a participant or beneficiary-

. . . .

(B) to recover benefits due to him under the terms of his plan, to enforce his rights under the terms of the plan, or to clarify his rights to future benefits under the terms of the plan. . . .

A close look at section 502 reveals that only equitable relief is available.53 Because it is the exclusive remedy, it causes many of the problems with claims involving managed care organizations.

When Congress considered ERISA, it looked at health benefits systems as they were being administered in 1974. If a person got sick, he went to the doctor, got the treatment he needed, and waited for reimbursement from his health benefit plan. If the health benefit plan did not approve the treatment, the plan member had to pay for the treatment out of pocket. Under this scheme, equitable relief was an appropriate remedy. If the plan wrongly withheld payment, the plan member, under ERISA, could recover his out-of-pocket expenses.

What Congress did not anticipate was that the country would move to the HMO/PPO health care systems. Now, when a person gets sick, he goes to a primary health care provider, who makes a recommendation on further treatment. A Utilization Reviewer then determines the cost appropriateness and necessity of medical care. If Utilization Reviewer denies necessary treatment, plan members may suffer injuries, further illness, or die. Then, when a wrongful death or medical malpractice claim is filed under state law, it is preempted as “relating to” employee benefit plans.

Remember under ERISA, only equitable relief is available. What would that amount to? The premiums the employee has paid for his health care plan? An award of paid premiums? Some compensation that would be for the loss of a leg, or a death in the family. Typical medical malpractice compensatory and punitive damages are simply not available under ERISA. Ironically, if an injured patient has no medical fringe benefits he does not face the ERISA obstacle. If he pays for his own medical care, then the denial of treatment would not “relate to” employee benefits, and a state law claim for medical malpractice would be valid.

Beginning with Alessi v. Resbestos-Manhattan, Inc.,54 and Shaw v. Delta Air Lines Inc.,55 ERISA was read so broadly that nearly all plaintiffs’ claims were held to be preempted by the federal statute.56 This reading was simply missing the purpose of the ERISA statute.57 Nevertheless, this misreading was affirmed and followed.58 Mackey v. Lanier Collection Agency & Service, Inc.,59 marked an all time high for ERISA preemption. The Mackey court held that the “mere mention of ERISA in a complaint will require preemption.”60

2. The New Paradigm and Successful ERISA Strategies

Because of the legal perversions that ERISA was creating, courts have begun to resurrect long forgotten principles.61 In New York State Conf. of Blue Cross & Blue Shield Plans v. Travelers Insurance Co.,62 the Supreme Court struck a blow in the name of federalism and mandated a presumption against preemption.63 Only in situations where it is absolutely necessary to provide federal legislation-because state legislation will simply not provide the consistency that the subject requires-should the federal government be able to reign over a state issue. According to the Court in Travelers, an incidental economic federal impact is not enough to justify federal jurisdiction. Only significant economic impact on benefits packages should trigger preemption.64 Travelers also abandoned “relates to” literalism and set a standard for looking to the structure and purpose of ERISA.65 This decision opened the door around ERISA. Now the test is when a state law binds ERISA administrators to specific choices, or in some way limits administrative discretion, it is preempted.66

The problem now is finding a way to structure a complaint to avoid preemption and recover damages for injured clients. The first step is to understand the “relates to” trap in the language of section 514. “Relates to” is virtually limitless; it has no definitive end. It’s like the house that Jack built. The cheese is related to the mouse that is related to the cat that is related to the house; therefore, the cheese and the house are related. Success in avoiding preemption requires cutting off the “relates to” logic. In 1997, in California Division of Labor Standards v. Dillingham, Justice Scalia addressed this concern, in dicta.67 He noted that the “relates to” language is particularly unhelpful and should cease to be the test courts use to determine whether a claim should be preempted. Instead, he suggested the test should be ordinary field preemption or conflict preemption analysis.68

In Bannister v. Sorenson,69 the Eighth Circuit reviewed past precedent and distilled six factors which can be used in preemption analysis. The use of these factors avoids the “relates to” problem. Consider: (1) Would the state law claim negate a provision of ERISA? (2) Would it have an undue effect on ERISA entities? (3) Would it have an overbearing effect on ERISA administrators? (4) Would it have a sizable economic impact? (5) Would it be inconsistent with provisions of ERISA? (6) Is the claim focused on an area of traditional state power? Considering these factors the claim is not preempted if litigation of the state claim would only minimally affect ERISA. However, any claims that impose duties on ERISA administrators that conflict from state to state are generally preempted.

Therefore, the key to avoiding the preemption trap is to critically ask yourself: “What would my claim have the defendants change about their conduct?” Then you must ask: “Would the claim require the defendant to institute a change which would sizably impact the economics or administration of an ERISA plan?” If the answer is yes, then you must change the nature of your claim. You must change it until the answer is “no.”

The Third Circuit case of Dukes v. U.S. Healthcare70 is an example of how pleadings can affect the outcome of a preemption battle. In Dukes, the plaintiff’s husband allegedly died because the defendants refused to perform prescribed blood tests that would have timely identified a dangerously high blood sugar level. The plaintiff claimed the HMO was vicariously liable under the agency theory for the acts of doctors who refused the test and directly liable for failure to properly select and screen the doctors.71

The defendant’s HMO removed the case to federal court claiming that not only was the claim expressly preempted by § 514 as “related to” an ERISA plan, but that it was also preempted by § 502 because the medical care allegedly denied was a “benefit” and solely enforceable by way of § 50272

The Dukes court distinguished between § 514 and § 502 preemption. Citing Metropolitan Life Ins. Co. v. Taylor,73 the court held that only § 502 so completely preempts state laws as to make them removable. “ERISA preemption under § 514(a) without more, does not convert [a] state claim into an action arising under federal law.'”74

Because of this, the Dukes court did not concern itself initially with defensive preemption dismissal, but only with removal jurisdiction and remand. If the claims were arguably preempted by ERISA, but not “completely” preempted, the court had no jurisdiction to hear the defensive preemption battle because the case had been improvidently removed.

The difference between preemption and complete preemption is important. When the doctrine of complete preemption does not apply, but the plaintiff’s’ state claim is arguably preempted under § 514(a), the district court, being without removal jurisdiction, cannot resolve the dispute regarding preemption. It lacks power to do anything other than remand to the state court where the preemption issue can be addressed and resolved.75

Thus the sole issue for the Dukes court was whether the plaintiff’s claims were preempted by the removal-worthy § 502. A reading of § 502 shows that it covers recovery of benefits due and enforcement and clarification of benefit rights. The court held that there was not § 502 preemption:

We are compelled to this conclusion because the plaintiff’s claims, even when construed as U.S. Healthcare suggests, merely attack the quality of the benefits they received: The plaintiffs here simply do not claim that the plans erroneously withheld benefits due. Nor do they ask the state courts to enforce their rights under the terms of their respective plans or to clarify their rights to future benefits. As a result, the plaintiff’s claims fall outside of the scope of § 502(a)(1)(B) and these cases must be remanded to the state courts from which they were removed.76

In Dukes the nature of the wrongful conduct (refusing to provide the blood test) could easily have been pled as a “denial of benefits due him.” Of course, this plaintiff’s attorneys in Dukes were smart enough to avoid such claims and only attack the behavior of the defendants as medical doctors, not as administrators. This is how one avoids the preemption trap – knowledge of the law and well-pled complaints.

Even when the facts of the case require pleading that benefits were withheld, there is still a possible way to avoid ERISA preemption. Normally these Utilization Review cases are lumped into § 502 of ERISA as “enforcement” of benefit rights. The way around § 502 is simply to show that a Utilization Review claim, where treatment was denied and injury resulted, is not seeking “enforcement” of benefit rights. It is simply seeking damages. One must persuade the court to look to the intent of ERISA rather than play the statutory construction rhetoric with “relates to.” The intent of Congress was to provide financial guidance and not medical guidance to ERISA plans. When this is clear to the court, the framework for a winning Utilization Review case is set. When a reviewer makes a bad medical decision, the harm should be remedied through the same avenues by which vicarious liability claims are remedied. These avenues provide compensatory and even punitive damages.77 The administration of the plan is not in question. Section 514 does not apply.

Although this argument makes good sense, its legal foundation is weak. A Utilization Reviewer bases his decisions on both the medical need for treatment and the associated costs. To divide that decision into two parts may be splitting hairs. While other torts accept the medical/monetary distinction, there is precedent that leans toward the notion that ERISA does not.78 To make that distinction require examination of the terms of a specific plan, and the Supreme Court has held that any law requiring examination of a plan’s terms are preempted.79

ERISA cases are now easier to keep in state court. But many claims are still preempted and there is a general sense that the law is unfair. Congress has recognized the problem and may do something about it. Several bills have been introduced onto the floor to establish minimum federal standards for HMOs and managed care insurers. The hope for these new pro-patient bills is to deter health insurers from compromising care in the pursuit of profits.80 If the courts cannot clean up the mess, the new millenium will surely bring with it health care legislation.

B. Products Liability

1. Tobacco

“WARNING: THE SURGEON GENERAL HAS DETERMINED THAT CIGARETTE SMOKING IS DANGEROUS TO YOUR HEALTH.” The Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act of 1969 requires this warning (among others) to appear on every pack of cigarettes sold in the United States. That act, along with the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act of 1965 was enacted to standardize regulations based on smoking and health. The acts imposed requirements relating to cigarette packaging and advertising. At the same time the acts preempted state law requirements with respect to the advertising and promotion of any appropriately labeled cigarettes. The acts prevented states from promulgating regulations regarding cigarette labeling.81 Each act has a section 5a, and each act has a section 5b. They have been recodified for legislative purposes,82 and are set forth in the following chart:

1965 Labeling Act

1969 Cigarette Smoking Act

(a) No statement relating to smoking and health, other than the statement required by section 4 of this Act, shall be required on any cigarette package.

(a) No statement relating to smoking and health, other than the statement required by section 4 of this Act, shall be required on any cigarette package.

(b) No statement relating to smoking and health shall be required in the advertising of any cigarettes the packages of which are labeled in conformity with the provisions of this Act.

(b) No requirement or prohibition based on smoking and health shall be imposed under State law with respect to the advertising or promotion of any cigarettes the packages of which are labeled in conformity with the provisions of this Act.

Historically, the acts were used as an all-encompassing shield, protecting cigarette manufacturers from any and all liability arising from state law causes of action. Only recently has the Supreme Court narrowed the scope of preemption in the landmark case of Cipollone v. Liggett Group.83

Rose Cipollone began smoking in 1942 and died of lung cancer in 1984. Before death she filed a complaint alleging that Liggett Group, Inc., and other cigarette makers

. . . breached express warranties contained in their advertising, because they failed to warn consumers about the hazards of smoking, because they fraudulently misrepresented those hazards to consumers, and because they conspired to deprive the public of medical and scientific information about smoking.84

In analyzing the claims, the court splintered into a confusing plurality. However, seven justices agreed that the 1965 act had no effect on common law claims and only preempted state “rule making bodies from mandating particular cautionary statements. . . .”85

Six justices agreed that § 5(b) of the 1969 act did preempt certain of Cipollone’s failure-to-warn claims and fraudulent misrepresentation claims, but did not preempt the warranty and conspiracy claims.86 “[T]he language of the [1969] act plainly reaches beyond [positive] enactments.”87

Cipollone had the effect of splitting tobacco cases into two categories: those that are preempted and those that are not. Most common law state tort claims survive preemption. However, any failure to warn or advertising claims still face federal preemption.88 The Court decided that what was actually preempted by section 5 of the 1969 Act was state regulation of cautionary statements. That is, states cannot make any rules regarding cigarette warnings. State police power, an area of traditional state occupation, was not preempted.89 Cipollone clearly bars failure-to-warn claims based on advertising. However, the door may be open for state law failure-to-warn claims based on packaging.90

In both the 1965 Act and the 1969 Act, section 5a deals with cigarette packaging and section 5b deals with advertising and promotion of cigarettes. The Court found that section 5b of the 1969 Act did have a preemptive effect, but the Court remained silent on section 5a of the 1969 Act. However, in dicta, seven members of the Cipollone Court agreed that section 5a of the original 1965 Act had no preemptive effect on common law tort claims.91 Section 5a of the 1965 Act reads: “No statement related to smoking and health, other than the statement required by section 4 of this Act shall be required on any cigarette package.” The wording of section 5a of the 1969 Act is exactly the same. Therefore, if the 1965 Act has no preemptive effect, neither should the 1969 act with respect to cigarette packaging.92

One should keep in mind that this argument remains untested in court. Allowing a state claim based on a package’s failure-to-warn may simply defeat the legislative purpose of the statute. Such a claim might encourage each state to set its own labeling standards, contrary to the legislative intent of federal uniformity.

The exact holding of Cipollone will be revealed and clarified in future litigation, but for now it is still under debate. Undebatable, however, is its impact on federal preemption in products liability claims.93 Cipollone will be most cited for is its resurrection of the presumption against preemption.94 Cipollone, in effect, held that when preemption is expressly addressed, congressional intent can be inferred. When a statute drafted by Congress contains express preemption provisions with a limited scope, no express preemption will be grafted onto other provisions of the statute. The other provisions may only preempt via conflict with state law. The Court will not infer any broader scope of preemption than what is actually written.95 When Congress expressly discusses preemption with regard to one aspect of a statute, it has effectively expressed its intent not to preempt other areas of the statute-Expressio unius est exclusio alterius (to express one is to exclude the other).96 This presumption against preemption has reached into other areas of products’ liability, from airbags to pacemakers.

2. Airbags and Motor Vehicle Safety

In 1966, Congress approved the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act in order to provide national uniformity in automobile manufacturing requirements.97 The Motor Vehicle Safety Act standards serve as minimum standards for motor vehicle safety.98 Over the years automobiles have incorporated numerous safety devices and modifications including airbags. Litigation relating to airbags typically involved the inadequacy of restraint systems and alleged that airbags or similar devices should have been installed in automobiles in addition to seat belts. More recently, litigants have alleged that certain designs of airbags are inadequate. Other cases claimed that the airbags caused the plaintiffs’ injuries.

These liability claims stem from the crashworthiness doctrine which first arose in Larsen v. General Motors Corp.99 The court in Larsen held that vehicles must be designed in a manner that provides adequate protection to its occupants. Manufacturers typically contend that restraint system claims are preempted. Until recently, the courts agreed.100 Few courts recognized state law claims in the presence of the Motor Vehicle Safety Act.101 While plaintiffs argued that their automobiles did not meet the stringent standards required to make them crashworthy, a manufacturer’s compliance with federal minimum standards generally snuffed out the claims. The result was that consumers would be hurt in auto crashes and could not be heard in court on their claim that their car should have had an airbag instead of a mere seat belt.

This preemption trend is hard to fathom in light of the statutory language at hand. Section 30103 of the act contains a provision preempting only less stringent state regulation and permitting more stringent state regulation:

(b) Preemption

(1) When a motor vehicle safety standard is in effect under this chapter, a State or a political subdivision of a State may prescribe or continue in effect a standard applicable to the same aspect of performance of a motor vehicle or motor vehicle equipment only if the standard is identical to the standard prescribed under this chapter. However, the United States Government, a State, or a political subdivision of a State may prescribe a standard for a motor vehicle or motor vehicle equipment obtained for its own use that imposes a higher performance requirement than that required by the otherwise applicable standard under this chapter.

(2) A State may enforce a standard that is identical to a standard prescribed under this chapter.102

The Motor Vehicle Safety Act also contains a savings clause which provides: “Compliance with any federal motor vehicle safety standard issued under this subchapter does not exempt any person from any liability under common law.”103

A more rational reading of these provisions has developed in the wake of Cipollone. Now, the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act is considered in light of the presumption against preemption. If Congress had intended to preempt design defect litigation it would have expressly stated so. Instead, it expressly preserved state common law in the savings clause. Congress certainly knew of design defect litigation in 1966, and yet, design defect litigation was not addressed in the act. Because it was not addressed and Congress in 1966 would have considered it part of state common law, it is not preempted. Courts are finding that the Motor Vehicle Safety Act was intended not to be exclusive of the common law, but rather, supplementary to it.104 In Tebbetts v. Ford Motor Co.,105 the plaintiff’s decedent was killed in an automobile accident. The plaintiff alleged design defect due to the lack of a driver’s side airbag. In reversing a trial court summary judgment, the New Hampshire Supreme Court determined that

. . . . Congress intended the Safety Act to be “supplementary of and in addition to the common law of negligence and product liability.” Larsen v. General Motors Corp., 3891 F.2d 495, 506 (8th Cir. 1968). Having determined that the preemption clause when read in tandem with the saving clause “provides a reliable indicium of congressional intent with respect to state authority, there is no need to infer congressional intent to pre-empt state laws from the substantive provisions of the legislation.” Cipollone, 112 S. Ct. at 2618 (citation and quotation omitted).

Because we must construe the preemption clause narrowly in light of the presumption against the preemption of state police power regulations, CSX Transp., Inc. v. Easterwood, 123 L. Ed. 2d 387, 113 S. Ct. 1732, 1737 (1993), and given the express utilization of the term “common law” in the saving clause, we agree with the analysis of those courts that have held that actions such as this are not preempted. See, e.g., Gingold, 567 A.2d at 330. 106

Thus, if one plans on filing a case implicating design and manufacture of a motor vehicle, one should generally become conversant with the Motor Vehicle Safety Act. Even if the current trend of courts is away from preemption, courts in any given jurisdiction may still cling to the notion of implied preemption. Even in jurisdictions following the new trend, one must be wary of a plethora of specific regulations, which may simply conflict with a cause of action and preempt it.

3. Pesticides

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) is a broad, total regulation of every aspect of the pesticide industry.107 If one is handling a claim involving pesticides, one should become familiar with the provisions of FIFRA.108 The act contains a provision, which has been held to have preemptive effect:

§136v. Authority of States

In general. A state may regulate the sale or use of any federally registered pesticide or device in the State, but only if and to the extent the regulation does not permit any sale or use prohibited by this Act.

Uniformity. Such State shall not impose or continue in effect any requirements for labeling or packaging in addition to or different from those required under this Act.109

With respect to pesticide labeling, not only does this section preempt state requirements “different” from federal law, but also it preempts state laws “in addition” to federal requirements. Unlike the Motor Vehicle Safety Act, FIFRA does not allow for more stringent, albeit consistent state labeling requirements. It is no wonder. FIFRA is incredibly comprehensive with respect to product labeling. Nine pages of the Code of Federal Regulations are devoted to specific warning language, placement of warnings, size and color of warning type, and many other minute details.110 One could try to apply the airbag argument to pesticides, but would soon run into insurmountable obstacles, because under FIFRA, a pesticide manufacturer is actually prohibited from using more stringent language than provided for by the Act. “Use of any signal word(s) associated with a higher toxicity category is not permitted except when the agency determines that such labeling is necessary to prevent unreasonable or adverse effects on man or the environment.”111

A significant number of federal cases have recently arisen after Cipollone to preempt injured persons’ claims against the manufacturers of pesticides. In Papas v. Upjohn Co.,112 workers were injured due to exposure from pesticides manufactured by the defendants. The workers’ claims were based on negligence, strict liability, and a breach of warranty. All of the claims impugned the inadequate labeling of the pesticides. Comparing section 136v to the Cigarette Labeling Act provisions analyzed in Cipollone, the court held the workers’ claims to be preempted.

The Papases concede that each of their negligence, strict liability, and breach of implied warranty counts alleges in part that Zoecon failed to warn users that its product contained certain harmful chemicals and failed to inform users to take appropriate precautionary measures. Those allegations, like the failure to warn claims in Cipollone, require the finder of fact to determine whether, under state law, Zoecon adequately labelled [sic] and packaged its product. This inquiry is precisely what section 136v forbids.113

The problem for most practitioners in pesticide cases is to find a defect in the product other than a marketing (labeling) defect. Design and manufacturing defects are difficult to come by when dealing with liquid or powdered chemicals. Most harm to persons is brought upon by improper handling, which is normally either consistent with or in violation of a label. Either way, it is not typically a manufacturers’ problem, but a problem for those who handle the chemicals.

One who seeks to avoid preemption can find guidance in certain cases on how to formulate a theory of liability and draft his pleadings. Jenkins v. Amchem Products, Inc., involved a farmer whose use of the chemical 2,4-D over a long period of time led to the development of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.114 He brought suit against the manufacturer alleging (1) negligence, (2) failure to adequately test the product to ensure it was free from harmful contaminants, (3) failure to warn plaintiff of the long-term exposure risks, and (4) strict liability. The trial court granted partial summary judgment based on FIFRA preemption. The court described its order as follows: “[R]eferring to plaintiff’s four legal theories as stated in the pretrial order, this ruling restricts theory 1 [negligence], leaves theory 2 [failure to adequately test] untouched, eliminates theory 3 [failure to warn], and restricts theory 4 [strict liability] to the extent it is based upon a failure to adequately warn or instruct.”115 The trial court next ruled on the defendants’ motion that all of the plaintiff’s remaining claims were inextricably related to the adequacy of the labeling. The court agreed and dismissed the entire case.116

In a detailed opinion, which included a survey of the post- Cipollone FIFRA cases, the Supreme Court of Kansas affirmed the dismissal and adopted a test set forth in the case of Worm v. American Cyanamid Co.117 To determine whether or not a plaintiff’s claim relates to labeling (and is preempted) versus some other defect in the product (and is not preempted), the following inquiry should be made: “. . . .whether one could reasonably foresee that the manufacturer, in seeking to avoid liability for the error, would choose to alter the product or the label.”118 While this test is subjective as to the reasonable foreseeability of a manufacturer’s actions, it still provides a plaintiff with guidance in avoiding FIFRA preemption in claims against pesticide manufacturers.

For a plaintiff’s attorney, the key is to claim a defect that is easier to fix by changing the product than changing the label. This will not be easy in most cases. For example, assume a can of roach spray contained extremely harmful carcinogens, which if breathed in, caused lung cancer. Normally, a lazy manufacturer would simply warn against inhaling the spray. However, a plaintiff may claim the product is defective because its liquid is too volatile and prone to becoming airborne when sprayed through a standard spray can nozzle. Certainly the defect claimed has nothing to do with the label. Nor can a manufacturer guard against this defect by changing the label. To fix the defect, the manufacturer must change the product. Another strategy to avoid preemption in such a case would be to sue the manufacturer of the spray can, claiming that the nozzle delivered the product in a volatile form and/or failed to incorporate a safety device, such as a respirator, with the product. In the latter case a clever defendant may claim that the respirator or the spray can is part of the packaging and thus covered by FIFRA. In general, plaintiffs who wish not to be removed to federal court and/or dismissed must avoid a pleading that impugns the labeling or packaging of pesticides. In short, plead around the label.

Only one case has found a state failure-to-warn claim based on failure to warn viable. In Ferebee v. Chevron Chemical Co.,119 the court allowed a state tort claim for damages caused by a herbicide. Even though § 136v(b) of FIFRA seems to expressly preempt state actions, the D.C. Circuit found that it did not. The court decided “Even if Chevron could not alter the label, Maryland could decide that, as between a manufacturer and an injured party, the manufacturer ought to bear the cost of compensating for those injuries that could have been prevented with a more detailed label than that approved by the EPA.”120 The court’s reasoning then followed that absent a “clear and manifest purpose” to preempt, state tort damages were not incompatible with federal law.121 One wonders what could be more clear and manifest than: “Such State shall not impose or continue in effect any requirements for labeling or packaging in addition to or different from those required under this Act.”122 Most subsequent cases have rejected the rationale in Ferebee.123

In pesticide cases, plaintiffs should seek out defendants other than manufacturers. They should sue distributors and, more importantly, applicators if possible. There are a number of cases which hold that FIFRA preemption does not apply to these other defendants.124 This author has successfully represented the victims of pesticides and avoided claims of FIFRA preemption by carefully selecting defendants and avoiding claims which relate to failure to warn.

4. Medical Devices